ClientEarth Communications

15th July 2021

Gas is not an alternative to fossil fuels. Gas is a fossil fuel.

With stock prices of coal and oil plummeting, the fossil fuel industry has increasingly moved its focus to so-called 'natural' gas. The industry is touting it as a greener fuel that will allegedly assist us to make the transition to clean energy.

But behind this veneer are huge climate and economic risks. With the gas lobby hard at work to secure several further decades of fossil fuel exploitation, it’s vital now more than ever that we set the record straight.

The name 'natural gas' hides the truth about the environmental damage caused by this commodity. Gas is natural in the sense that it naturally occurs within the Earth’s surface – just as oil and coal do. And like oil and coal, exploiting it and burning it has gargantuan climate impacts: burning gas emits far more carbon dioxide than we’re led to believe.

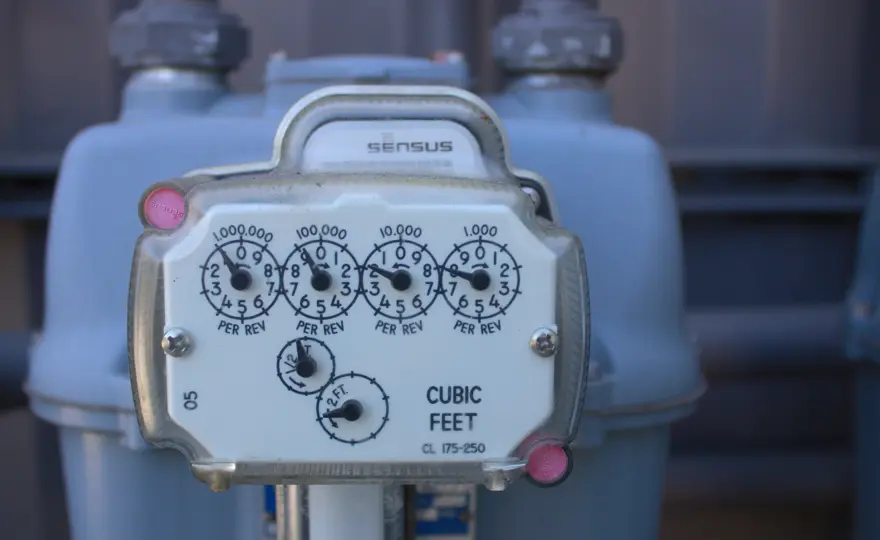

But there is another threat: in the process of extracting, transporting, and distributing gas, potent methane – its main component – leaks into the atmosphere. Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas with a global warming potential 86 times that of carbon dioxide over a 20-year period.

Weak laws around methane regulation mean that in most countries, companies are not required to accurately report on, and effectively limit, methane leaks in the energy system. Independent scientific studies suggest that methane emissions from the oil and gas sector are being vastly underreported, and that using gas for energy could actually be as climate-damaging as coal.

In the fight against climate change, this kind of information gap opens the door to existential mistakes.

In many European countries, the gas industry has misled decision-makers and populations with the notion that gas is needed in order to fill a gap between decreasing coal and oil production and ramping up renewable forms of energy – hence the so-called “bridge” label. But this argument doesn’t stack up.

There are viable, clean alternatives to gas, which are either already cheaper or very soon will be. In most of Europe, these renewable alternatives are readily available. Gadgets like batteries will store surplus energy from renewables, and release it when required. Besides, as countries improve their energy efficiency, they require less gas.

More gas investment distracts from the task of cleaning our energy system, and diverts crucial public funding away from clean alternatives and funnels it into more fossil fuels. In less than a decade, €440 million of EU public funding has been spent on gas projects which have either failed or been put on hold – a huge sunk cost to be borne by EU taxpayers.

If we are to achieve our global climate goals, half of the world’s remaining gas resources must remain unused. Each cubic metre of gas extracted just drags us further away from our climate goals.

New gases, notably hydrogen, are being marketed by the gas industry as clean, soon-to-be alternatives to gas. Governments across the world are weighing up how much of a role hydrogen will play in our future energy mix.

There are many shades of hydrogen, including grey hydrogen – obtained from methane – or blue hydrogen – produced by splitting natural gas at high temperatures and storing carbon dioxide. But these still release large amounts of carbon dioxide and methane to the atmosphere.

It is unclear whether green hydrogen – hydrogen produced from renewable energies, with low associated carbon emissions – will be available at a reasonable cost and at scale in the near future.

It therefore cannot be used as an excuse to continue deploying mass gas infrastructure. Doing so risks diverting attention and resources from genuinely clean alternatives like wind and solar power.

We’ve already taken action against gas.

We stepped in to stop the expansion of a huge and controversial new plastics plant in Antwerp, Belgium. Ineos – the company behind the plant – relies on massive imports of US shale gas in the form of ethane, which it breaks down into ethylene to make plastics.

We took the UK government to court over its approval of what would have been Europe’s largest gas-fired plant in North Yorkshire. Since then, the company behind the mega-plant – Drax Power – has confirmed that it will scrap its plans.

In the EU, we work to get better laws put in place. The EU has committed to 55% emissions reduction by 2030 compared to 1990 levels, which would require the bloc’s consumption of gas to reduce by 30% by 2030.

But European Union policies still favour gas infrastructure. The list compiling the EU’s “most important” energy infrastructure projects – those eligible for EU funding and fast-track permitting– still features a lot of gas. That represents a potential overinvestment of tens of billions of euros, supported by EU taxpayers’ money.

We are seeing a fierce local opposition emerge, driven by environmental, health and geopolitical concerns, targeting several pipeline projects, which would increase gas imports from outside the EU.

Ultimately, our goal is to remove all distortions that favour gas by removing access to public funding and support, regulating its full lifecycle emissions – including methane – and promoting fair competition with clean alternatives.

If we want to achieve our climate goals, we have to look beyond all fossil fuels – and that means steering clear of gas.