Dimitri de Boer

22nd September 2021

“China will not build new coal-fired power projects abroad.” President Xi Jinping’s announcement at the UN General Assembly on 21 September 2021 was clear and simple. With China pulling out of overseas coal financing, the last big source of money for such projects is gone. The announcement contains no loopholes, no exceptions.

The days of new coal plants popping up around the world are over. Attention will now shift to the rapid deployment of renewable energy solutions. Today the global climate community is celebrating.

This is incredibly important. In 2017 - 2019, China was pumping around US $6-8 billion per year into new coal power plants everywhere. It was easily the largest financier and builder of new coal. The Paris Agreement targets appeared to be melting like snow in the sun. With China as a provider of new coal finance, many developing countries continued to incorrectly view coal as the low-cost development pathway, oblivious of the rapidly changing economics of renewable energy. China’s decision to pull out of coal will send shockwaves through the global energy community. I expect new coal plants to reduce to a trickle. Given the high risk of default and stranded assets, it would take a very bold investor to continue to back new coal plants. And the stranded asset risk isn’t limited to coal – basically all new fossil power plants are exposed.

This means that developed and developing countries alike will now focus on the deployment of renewable energy. The timing is excellent, as so many countries need to boost their economies for post-pandemic recovery. In developing countries, renewable energy is needed to power economic growth. In developed countries, it is needed to replace outdated fossil capacity.

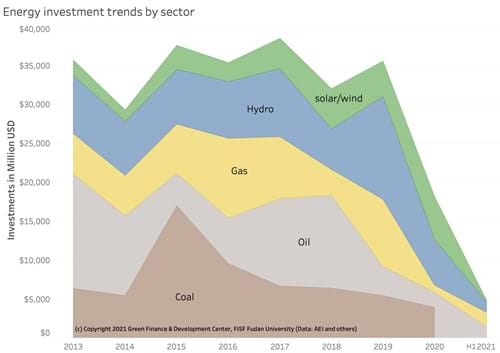

Chart: Energy investments in the Belt and Road Initiative, 2013 – 2021

![]()

![]()

Source: Green Finance & Development Center, FISF Fudan University

The move opens the way for huge investment in renewables and provides opportunities to address the key challenges: How to balance a grid with a high share of renewables? How to deal with storage? What about countries with very few sources of renewable energy? The net result will hopefully be that many developing countries leapfrog directly to low-carbon energy systems.

This will shift the needle on global warming. Could this mean the Paris targets may be back in reach?

I believe there are three main reasons for China’s decision: rising awareness around the risks of climate change to China; the realization that the economics of coal have really shifted; and reputational and diplomatic considerations.

The economic argument is key: China is no longer doing anyone a favour by building new coal. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the world’s largest infrastructure programme, is intended to help developing countries, and the argument was always that it would be unfair to deny them low-cost power.

But now that coal is no longer competitive, why would China want to saddle developing countries with outdated technologies which could easily turn into liabilities in the near future? Last year, we conducted an assessment of the financials of new coal power in Pakistan with Beijing Institute of Finance and Sustainability, and found that the default risk is as high as 30% by 2030, further rising in the future.

The Chinese government underwrites these projects, through state backing of the key development banks, and through insurance provided by export credit agencies. Coal assets are seriously exposed to the climate transition.

On top of that, since late 2020 many other countries have also quickly announced that they’ll no longer build coal. Since Xi’s pledge for carbon neutrality one year ago, the G7, as well as Japan and Korea, have made similar announcements. Many developing countries even announced they no longer want coal, including Pakistan, and Indonesia, and others.

China really wants to make a positive contribution to global environmental governance, and wants to be seen as a responsible actor in the global fight against climate change. And while China is trying hard to curb emissions at home, it would hardly make sense to help other countries increase their emissions.

The UN General Assembly is a very suitable forum, and the timing ahead of COP26 in Glasgow is excellent. China’s wants to make its contributions to global climate action on its own terms, and it considers the UN the appropriate venue for making such announcements.

Interestingly, China already stopped investing in new coal overseas since the beginning of 2021, apparently following internal instructions from the central government to the state-owned financial institutions.

Xi’s announcement at the UN is China’s first public confirmation of this new policy. He has made a formal commitment to the international community. In the Chinese context, this means that the decision is set in stone. It alleviates worries that China might backslide, or that there could be exceptions to the rule.

My understanding is that all new investments in overseas coal were put on hold at the beginning of the year, after the leadership was presented with various assessments which highlighted the urgent case for doing so. Since then, debates have taken place with key stakeholders, and further assessments. Some powerful state-owned companies possess the world’s most advanced coal power generation technology – they may have argued for continued investments in coal. Most other stakeholders would probably have been in agreement with the coal ban.

The international community has also made its position clear. UN secretary-general Guterres specifically asked for an end to coal financing. The UNDP has cooperated with the Chinese government on aligning the BRI with the sustainable development goals. EU vice-president Timmermans had also asked for an end to new coal in the BRI, and that was also the main ask of US climate envoy John Kerry when he visited China two weeks ago.

China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment in 2018 established the BRI International Green Development Coalition (BRIGC), an international platform between China and partners, with as its primary objective to green China’s overseas investments. ClientEarth has closely cooperated BRIGC and the World Resources Institute, on developing a new policy known as Green Development Guidance for BRI Projects. The first phase study report was published in December 2020, and recommended to place coal investments on an exclusion list. In February 2021 we also prepared a specific recommendation to put a ban on coal in China’s overseas investments, together with BRIGC and China’s National Center for Climate Change Strategy and International Cooperation (NCSC). That note really drove home the economic argument.

China’s environmental advisors have also been pushing very hard on this. Since 2018, the China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development (CCICED), a senior international advisory body to the State Council, has carried out studies on climate change, green finance, and greening the Belt and Road Initiative, and has made various recommendations about aligning the BRI with the Paris Agreement, and to phase out coal investments. Numerous other Chinese and international environmental advocates have made the same case.

Some people have asked me if it’s still possible for China to finance new coal overseas. That’s no longer possible. However, projects which have already started may still be completed.

And I don’t think other countries will finance new coal either. Japan may be the only other country which has been somewhat ambivalent, but the G7 has hammered Japan on this, and given China’s decision to drop coal, I don’t think it is tenable for Japan to continue to do so.

In theory, it’s still possible that new coal plants would be approved within China. But I don’t believe there will be many, if at all. China is already struggling to meet the climate targets it has set for 2025, and it is actively clamping down on new high emissions projects, with the central government deploying some of the most powerful tools at its disposal. And we just learned that China’s public interest prosecutors, who bring thousands of environmental cases every year, are eyeing climate litigation.

On top of those efforts, I would suggest the option for China to conduct a Central Environmental Inspection-led review of all high emissions projects which have been approved in the past years, both within China and overseas. Projects which haven’t yet or only partly started construction, or which are at great risk of becoming a liability, might still be canceled. Every coal plant will contribute to increased climate risk, and lead to vested interests in a heavily polluting business model. Dropping them now may be a tough choice, but it may prove to be much more economic than closing them later.

China is anticipated to submit its updated NDC ahead of the Glasgow COP26. Hopefully China will present a clear roadmap, coupled with absolute targets for total GHG emissions.

China’s decision to stop building coal plants overseas is a watershed moment which will boost global confidence in the climate transition. New coal power is no longer an option, so all other forms of energy will be in greater demand, accelerating the deployment of renewables like solar and wind. Investors will think twice about further investments in all fossil fuels.

And the climate agenda continues to be very urgent. To limit warming to 1.5 C, we need to reduce global carbon emissions by 2030 by 45% over 2005 levels, but the world appears to be falling far short of this target, with current NDCs possibly leading to a 16% rise in emissions by 2030.

China’s decision on coal overseas will help the world in achieving a green post-covid economic recovery. It will hopefully also boost its domestic coal phase out, and inspire other countries to further accelerate their climate transition and to provide more financial and technical support to climate mitigation and adaptation in the developing world.

With the world’s major powers competing for who makes the greener overseas investments, the dream of true sustainable development may finally be coming within reach.